They grew up side by side in a small house on Bethel Avenue in Merced, California. Same bunk beds. Same peeling wallpaper. Same view of the dusty road stretching toward the distant silhouette of Yosemite. Same parents, same prayers, same quiet town where nothing bad was supposed to happen.

But on December 4, 1972, that illusion was ripped apart.

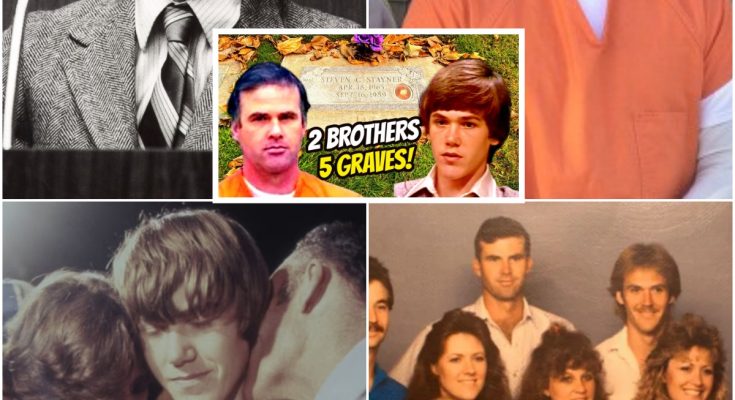

That night drew an invisible line through the Stayner family — a line that would separate two brothers forever. On one side was the boy who vanished, swallowed by a stranger’s cruelty and reborn as America’s symbol of hope. On the other, the brother who stayed — silent, forgotten, and slowly unraveling in the shadows of that hope.

It’s one of the most disturbing paradoxes in American crime: the boy who endured seven years of captivity became a hero; the boy who slept safely in his own bed became a k!ller.

This is their story — two lives twisted together by fate, tragedy, and the terrible ways trauma echoes through time.

Steven Stayner was seven years old — freckled, bright, curious — when he was approached by a man with kind eyes and a church pamphlet.

It was a cold December afternoon in Merced. He was walking home from school when a stranger stopped him. The man introduced himself as “Reverend Poorman” and said he was collecting donations for the church. Another man waited in a nearby car — Kenneth Parnell.

Parnell told Steven he wanted to take him to his parents. They climbed into the car, and from that moment, Steven’s world stopped being his own.

For seven years, Parnell moved him from town to town across California — sometimes posing as his father, sometimes leaving him alone in motel rooms. He cut Steven’s hair, changed his name to “Dennis Parnell,” enrolled him in schools under false papers, and fed him the lie that his parents didn’t want him anymore.

He was only a child. He believed it.

And yet, something inside him never fully surrendered.

He learned how to smile when it was expected. He learned how to hide the pain. He learned how to wait — quietly, carefully — for a chance to be free.

That chance came in 1980, when Parnell kidnapped another boy — five-year-old Timothy White. Steven, now fourteen, saw in Timothy what he used to be: small, scared, and lost.

One night, while Parnell was away, Steven took Timothy by the hand and ran. They walked for miles through the rain, across backroads and empty streets, until they found a police station in Ukiah, California.

The words Steven spoke to the officers would become legendary:

“I know my first name is Steven.”

The world would never forget them.

When news broke, America wept.

A missing child had come home. The boy who vanished into nothing had returned — alive, brave, a savior to another child.

Television cameras swarmed Merced. Neighbors brought casseroles. Churches held vigils. Steven’s parents, Del and Kay, clung to him in front of reporters, trembling with joy and disbelief.

For a brief, shining moment, Steven Stayner was a national hero.

Hollywood came calling. A TV movie, I Know My First Name Is Steven, aired in 1989 and became one of the most-watched programs of its time. People sent letters, gifts, prayers. He was the embodiment of resilience — the boy who escaped the monster and came home.

But behind the headlines, Steven struggled. He’d missed seven years of growing up. He was fourteen, trapped between two worlds — too young for adulthood, too old for childhood.

He couldn’t fit in at school. He slept with the lights on. He avoided hugs. He smoked. He drank.

Still, those who knew him said he carried a strange light — a humor that surprised people. He joked, teased his friends, fell in love, got married young, and had two children of his own.

He tried to rebuild what was stolen from him. And in many ways, he succeeded.

But trauma doesn’t vanish. It burrows deep — quiet, patient, waiting.

While the world adored Steven, another story was unfolding quietly at the Stayner home.

Cary, his older brother, was eleven when Steven disappeared.

At first, people pitied him — the brother left behind. But pity has an expiration date.

In the years that followed, while police searched for Steven, while neighbors whispered, while the press hounded his parents, Cary stayed invisible.

He watched his mother bake birthday cakes for a boy who wasn’t there. He watched his father leave food by the window, hoping a miracle would find its way home.

And when that miracle finally did, Cary was left standing outside the camera’s frame — literally. In photo after photo, Steven beams with his family, while Cary stands off to the side, half-shadowed, unsmiling.

“He just looked… detached,” recalled a neighbor. “Like he’d been replaced in his own family.”

Cary’s pain was quieter — no headlines, no rescue, no applause. While Steven’s trauma was public, Cary’s was invisible. And invisibility can rot the soul.

He grew into a tall, awkward teenager. He picked at his scalp until bald spots appeared. He couldn’t look people in the eye. He developed strange habits, paranoid thoughts, dark fixations.

But Merced was a town that didn’t talk about mental health. Cary was “the weird one.” The odd kid. The boy who “never got over it.”

He got jobs. Lost them. Worked at a glass company, a pizzeria, a nature lodge. He loved the wilderness — it was the only place that made sense to him. The woods didn’t ask questions.

Years later, friends would recall him saying things like, “I just want to disappear into the mountains.”

They thought he was being poetic.

He wasn’t.

In 1989, tragedy struck again.

Steven, now twenty-four, was riding his motorcycle home from work when a car turned suddenly in front of him. He died instantly.

The same news stations that had once celebrated his survival returned to Merced. America mourned. Candlelight vigils, documentaries, obituaries — all for the hero who cheated death once but not twice.

And once again, Cary watched from the edge of the crowd.

He didn’t cry at the funeral. He didn’t speak. He just stared — not at the coffin, but at the cameras.

To the public, Steven’s death was an accident. To Cary, it was something else: proof that even miracles don’t last.

Psychologists later suggested that this moment — watching the nation grieve his brother all over again — might have been the point of no return.

Whatever fragile balance he’d kept since childhood snapped.

In the years that followed, Cary drifted deeper into isolation. He moved out of the family home, lived out of motels, took odd jobs around Yosemite.

Coworkers said he was quiet, polite, strange. “He could stare at a river for an hour,” one said. “You never knew what he was thinking.”

They were right.

February 1999.

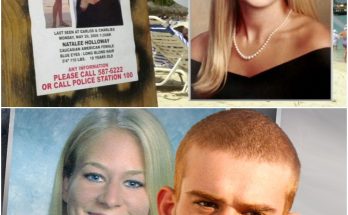

Three women — Carole Sund, her fifteen-year-old daughter Juli, and their Argentine friend Silvina Pelosso — vanished while vacationing near Yosemite National Park.

The search drew national attention. Helicopters. Posters. FBI involvement.

Weeks later, their rental car was found burned in a remote area. Inside were two charred bodies. Months later, the third body was discovered, throat slit.

Then, in July, another woman — Joie Armstrong, a young nature guide — was found decapitated near her cabin.

The public was horrified. Yosemite — the crown jewel of California’s wilderness — had become a hunting ground.

The FBI launched one of the largest manhunts in California history.

And then, on July 24, 1999, they made the arrest.

The suspect was a handyman who worked at the Cedar Lodge, near Yosemite’s entrance. A quiet man. Kept to himself. Always wore a cap.

His name: Cary Stayner.

The older brother of America’s miracle child.

When agents questioned him, Cary didn’t resist.

He didn’t plead innocence. He didn’t ask for a lawyer.

He simply said:

“You guys got me. I’m sick.”

Over hours of interrogation, he confessed in chilling detail. He’d lured the three tourists from their motel room, bound them, raped them, strangled them, and dumped their bodies. Later, he’d killed the park guide, Joie Armstrong, to satisfy what he called “the overwhelming urge.”

When asked why, his voice barely rose above a whisper:

“I’ve always wanted to kill. Ever since I was a little kid.”

The room fell silent.

Even the seasoned FBI agents — men who’d heard every kind of confession — later admitted they’d never encountered anything like it.

How does that happen?

How does a boy raised in the same home as a hero become a serial killer?

Experts debated it for years. Some said Cary suffered from untreated schizophrenia or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Others pointed to deep childhood trauma — the kidnapping, the grief, the years of being invisible.

Dr. Katherine Ramsay, a forensic psychologist who later studied the case, called it “a perfect storm of neglect and envy.”

“Cary was living in a house haunted by Steven’s absence,” she explained. “Then he was living in a house haunted by Steven’s fame. Either way, he was the shadow.”

In court, prosecutors called him methodical, remorseless, manipulative. The defense called him broken — a man shaped by trauma he never asked for.

The jury called him what he was: guilty.

Cary Stayner was sentenced to death in 2002. He remains on death row at San Quentin State Prison.

Del and Kay Stayner — the parents who’d once held their lost child in front of a nation — retreated into silence.

They buried one son, visited another behind bars, and tried to live in a town that could never forget their name.

“We’ve been through things no one should,” Del once told a reporter. “You lose one son to evil, and the other becomes it. What do you even pray for after that?”

The Stayners stopped giving interviews. The media moved on. But in Merced, their story never died.

Even now, locals speak of them with hushed voices — a mixture of pity, fascination, and fear.

“Everyone wanted to talk about Steven,” said a neighbor. “Nobody knew what to say about Cary.”

The contrast remains one of the most haunting in true-crime history.

Two boys. Same blood. Same childhood.

One faced unimaginable horror and found compassion.

The other faced ordinary grief and found darkness.

It forces the question: what makes a person who they are? Is it experience? Choice? Fate?

Psychiatrists call it differential resilience — how some people break and others bend. But words can’t explain the image burned into America’s memory: two brothers from the same home, two paths no human story should contain.

In a way, both were victims of the same event. One was taken by a stranger; the other by the silence that followed.

Decades later, the Stayner story still echoes through American culture.

In classrooms, it’s taught as a case study in trauma and criminal psychology. In documentaries, it’s retold as a tragedy of contrasts — light and shadow, hero and monster.

But in Merced, it’s still personal. The old Stayner house is long gone, replaced by a newer home, yet locals swear the air around that street feels heavy. Like the past is still breathing there.

Steven’s children grew up quietly. They’ve spoken little about their father, choosing privacy over fame. One of them once said, “He wasn’t a hero to me. He was just Dad — and that’s enough.”

As for Cary, he spends most days in silence, drawing landscapes in pencil. He told a journalist once, “I still dream about Yosemite. I dream I’m free there.”

But the truth is, neither brother was ever truly free.

Steven escaped one prison, Cary built another inside himself.

In the end, the Stayner story isn’t just about crime. It’s about the limits of human endurance — how love and trauma, nurture and neglect, can twist into something unrecognizable.

It’s about how two boys can grow up under the same roof, with the same love, and become reflections of opposite worlds.

One brother saved lives. The other destroyed them.

One was loved by millions. The other was forgotten until it was too late.

And in the middle of it all — a small California town that believed evil was something that happened elsewhere.

If you drive down old Highway 140 toward Yosemite, you’ll pass through Merced — a place that still looks ordinary. Gas stations. Orchards. The hum of small-town life.

But somewhere beyond those fields, two stories are still buried side by side.

The boy who said, “I know my first name is Steven.”

And the man who whispered, “I’ve always wanted to kill.”

The same blood runs through both.

And maybe that’s the hardest truth to face — not that monsters are born elsewhere, but that sometimes, they’re raised under the same roof as angels.