The Final Photograph: The Night the FBI Ended America’s Most Wanted Man

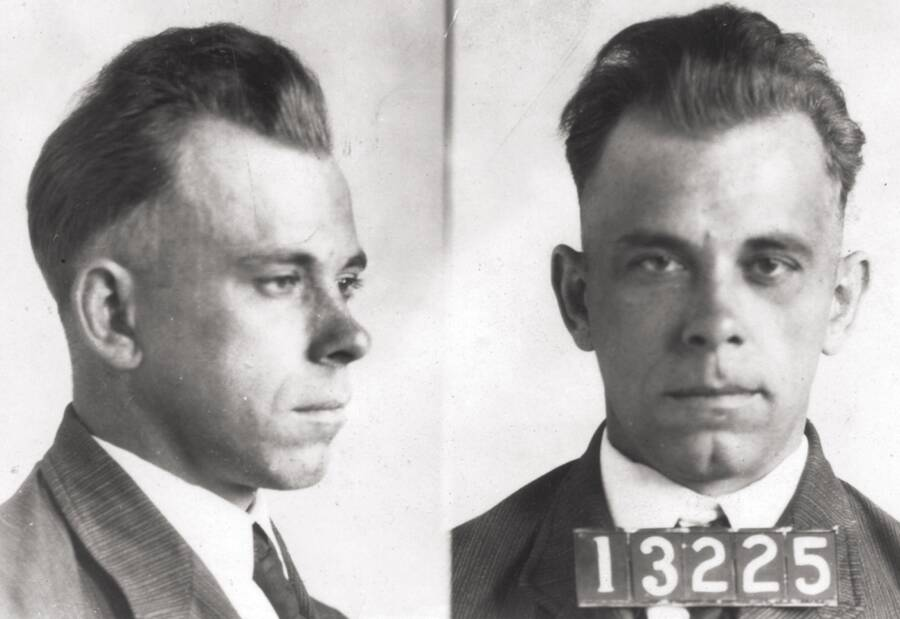

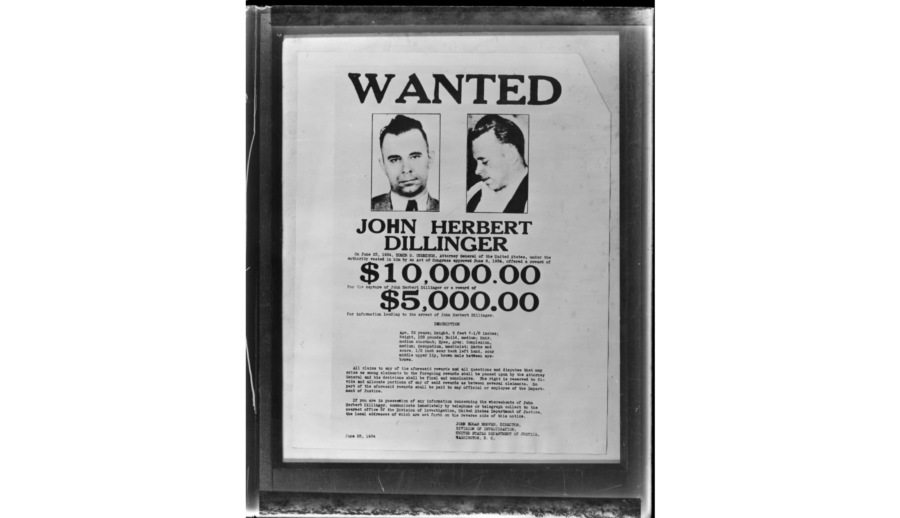

It was July 22, 1934. The humid Chicago night was still buzzing with the excitement of a Sunday crowd leaving the Biograph Theater. A camera flash went off just as a crowd began forming around a motionless figure sprawled on the sidewalk — face down, his fedora knocked to the side, his blood pooling beneath the streetlight glow. The man was John Dillinger, once called “Public Enemy No. 1.”

The photo, taken moments after the gunfire stopped, captured the dramatic end of a man who had terrified banks, taunted police, and thrilled the American public during the Great Depression. Onlookers craned their necks, reporters jotted feverishly, and federal agents stood stiffly as they guarded the body that had once symbolized rebellion against a broken system. That haunting image — a dead outlaw surrounded by flashing bulbs — marked the end of an era and the birth of a new kind of law enforcement legend: the rise of the FBI.

John Dillinger’s Early Life: From Mischief to Mayhem

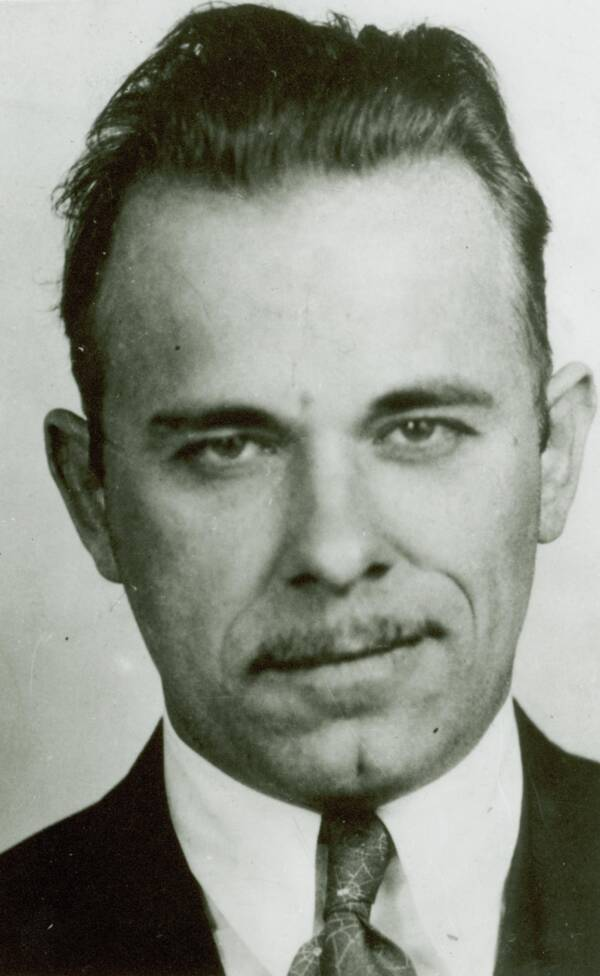

John Herbert Dillinger was born on June 22, 1903, in Indianapolis, Indiana. Raised by a grocer father and a mother who died when he was just three, Dillinger grew up restless and defiant. His father’s strict discipline alternated with indulgence, leaving young John torn between craving freedom and resenting authority.

As a boy, he led a group of neighborhood troublemakers called “The Dirty Dozen.” They stole coal from trains and caused mischief around town. By his teens, Dillinger dropped out of school and began working at a machine shop, where his boredom and taste for risk deepened. His father, hoping a quieter life might reform him, moved the family to a farm near Mooresville, Indiana — but country air couldn’t tame him.

He began drinking, fighting, and stealing cars. In 1923, after getting caught joyriding in a stolen vehicle, Dillinger joined the Navy to avoid jail. But discipline never suited him; he deserted within five months. When he returned home, he met and married 16-year-old Beryl Hovious. Domestic life didn’t last long. Money was scarce, and the young couple’s struggles pushed Dillinger toward darker opportunities.

Video : JOHN DILLINGER – Public Enemy Number 1

The First Crime That Changed Everything

In 1924, Dillinger teamed up with a friend, Ed Singleton, to rob a local grocer. The plan went wrong. They were quickly caught, and while Singleton pleaded not guilty and got just two years, Dillinger confessed on his father’s advice — earning himself a harsh sentence of up to 20 years in prison.

Behind bars, the young man hardened. Surrounded by experienced criminals, he learned everything he could about robbing banks, forging plans, and using weapons. When he walked out of prison eight years later, he wasn’t just angry — he was educated in crime.

“Prison didn’t reform me,” Dillinger would later say. “It taught me how to be a better criminal.”

Public Enemy No. 1: The Birth of an Outlaw Legend

Upon his release in May 1933, John Dillinger wasted no time. Within weeks, he robbed his first bank in Ohio, stealing $10,000. The thrill, the risk, and the attention hooked him instantly. By the end of that summer, he and his growing gang had robbed multiple banks and grocery stores across the Midwest.

Even when he was captured that fall, the story didn’t end. His gang disguised themselves as state police officers and broke him out of jail in a daring daylight rescue — a stunt that made national headlines. Soon after, Dillinger’s crew went on a spree that included over a dozen bank robberies and several deadly shootouts.

They looted police arsenals in Indiana, equipping themselves with Thompson submachine guns and bulletproof vests. They even used custom-built getaway cars — a shocking innovation for the time. For the public, Dillinger became a mix of Robin Hood and Hollywood star. Newspapers chronicled his every move, painting him as both villain and folk hero.

But to J. Edgar Hoover, head of the newly formed Bureau of Investigation, Dillinger was the perfect test case. Bringing him down would prove the Bureau’s worth and justify its transformation into what would soon become the FBI.

The Trap at the Biograph Theater

The beginning of the end came thanks to a desperate informant — Anna Sage, a Romanian-born brothel owner facing deportation. She reached out to the Bureau with an offer: she’d reveal Dillinger’s location if they helped her stay in the U.S.

On July 22, 1934, she told agents that Dillinger would be at the Biograph Theater with her and another woman, Polly Hamilton, to see Manhattan Melodrama, a gangster film starring Clark Gable. Sage promised she’d wear an orange dress so they could identify her — though under the neon lights, it appeared blood red.

At 10:30 p.m., the trio emerged. Agent Melvin Purvis, waiting near the exit, gave the signal by lighting his cigar. The agents closed in. Dillinger, realizing too late what was happening, reached for his gun. Three bullets struck him — two in the chest and one near the eye.

He stumbled a few steps before collapsing onto the pavement. Within minutes, John Dillinger — the nation’s most wanted man — was dead.

Video : The Bizarre Death of Bank Robber John Dillinger

The Aftermath: Chaos, Blood, and Legend

Crowds gathered almost instantly. Some people cheered. Others cried. According to eyewitnesses, fans dipped handkerchiefs in his blood as macabre souvenirs. Journalists raced to their telephones. Within hours, news of Dillinger’s death spread across the country.

Agent Purvis, who had led the operation, became an overnight celebrity. “I’m glad it’s all over,” he reportedly said. Hoover, meanwhile, used Dillinger’s death to transform the Bureau’s reputation — promoting it as a modern, scientific, and unstoppable force.

Dillinger’s funeral in Indianapolis drew more than 5,000 mourners, despite efforts to keep it private. He was buried beside his parents, his coffin encased in concrete to deter souvenir hunters. Even decades later, conspiracy theories swirled — some claimed the body wasn’t really his, that the FBI had killed the wrong man. But DNA testing later confirmed what history already knew: John Dillinger’s story ended that night outside the Biograph.

The Legacy of an American Outlaw

John Dillinger wasn’t just a criminal — he was a mirror reflecting America’s pain during the Great Depression. To some, he was a ruthless killer who deserved his fate. To others, he was a symbol of rebellion, a man who took from corrupt banks and made the government sweat.

In less than a year, he and his gang had robbed over a dozen banks, stolen $500,000, killed ten people, and wounded seven others. His crime spree forced the creation of a stronger federal law enforcement system — one that would evolve into the modern FBI.

But perhaps the most haunting part of Dillinger’s story is how aware he was of his own fate. “I’m traveling a one-way road,” he once told a friend. “And I’m not fooling myself about where it ends.”

He was right. It ended with flashbulbs, gunfire, and a blood-stained sidewalk in Chicago. But that photograph — the one taken moments after the shooting — still lingers as more than evidence. It’s a reminder of how legends die, and how America can’t seem to stop making them.

In the end, John Dillinger wasn’t just shot down outside a movie theater — he became one.